Evidence-based philanthropy. To some, that phrase offers the promise of long-overdue rigor. If the first principle of philanthropy and social impact is to do good, then evidence-based philanthropy ensures that we honor its corollary: Do no harm.

To others, that phrase represents all that is going wrong with philanthropy and social innovation — the rise of the ivory-tower theorists and technocrats whose logic models and fixation with metrics blind them to real-world knowledge and common sense.

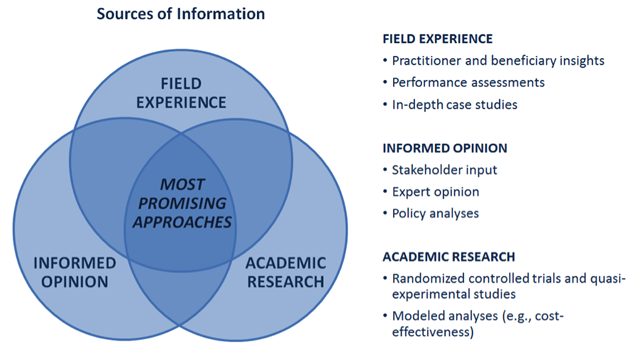

It’s time to rethink that pesky E word: evidence. A broader definition can include three circles of evidence to identify the most promising approaches for evidence-based philanthropy.

Evidence = Observations

The problem is that “evidence” means different things to different people.

For a veteran program manager, evidence might mean 30 years of seeing what has and hasn’t helped the people her nonprofit serves. For an individual donor, evidence might be seeing a class of low-income students he has supported since kindergarten graduate and become the first in their families to attend college. For an epidemiologist, evidence might be the results of a randomized control trial study proving the causal link between use of insecticide-treated bed nets and reduction of deaths due to malaria.

We spend a lot of time arguing over what kind of evidence matters most. But those arguments miss the mark. Each of the examples above is a relevant and valid approach to evidence. They simply answer different questions.

Field experience provides answers to questions like, “Who in the community will make or break the program’s success?” Informed opinion answers questions such as, “What issues should we prioritize?” and “What conditions signal that now is the time to act?” Traditional academic research answers, “Did our activities make a difference, and are we sure it wasn’t just due to chance or some other factor?’

In all of these cases, “evidence” is the result of careful observation, providing answers that give people confidence that what they are doing is right and leading to the change they seek.

And if one role of philanthropy is to solve the tough problems—those that remain despite government and business efforts—we need all the answers we can get.

Broadening the Definition of Evidence: Three Circles of Evidence

Here at the Center for High Impact Philanthropy, “evidence-based” has always meant accessing the best available information from three different sources, or circles of evidence:

- Research or scientific evidence such as the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and statistical models designed to link cause and effect.

- Field experience such as the practical knowledge of beneficiaries and program providers. These insights help explain how programs work in real-world conditions, when human behavior and implementation challenges come into play.

- Informed opinion such as the views of policymakers or other stakeholders whose perspectives provide context for evaluation results and field experience.

Each source of evidence has its strengths and limitations. For example, the results of a randomized control trial study may definitively show that use of a bed net reduces malaria or that a particular program increased graduation rates among a cohort of children at risk for dropping out. But it’s the observations of a village grandmother or community health worker that help us understand how to prevent people from using that bed net as a fishing net; it’s the insight of a great teacher or counselor that helps us recognize what a 9th-grade girl in East Palo Alto needs to succeed and how that might be different from what a 9th-grade boy in North Philly needs.

And while the beneficiaries themselves may not know the latest metrics, policy trends, or strategic planning behind a particular nonprofit or funder’s work, they are the ultimate authorities on whether a change created by a program represents a meaningful improvement in their lives.

So next time you see an argument about the E word, think of this: Rather than simply celebrating the advance of strategy and more rigorous evaluation in philanthropy, or defending the primacy of instinct and practical wisdom, let us propose a third way. Broaden what you mean by evidence. Because no matter what issue or cause you care about, the more each source of evidence—research, informed opinion, field experience—points to the same path, the more confident we can all feel that we’re headed in the right direction.