Young adulthood, between the ages of 16 to 24, is a period of transition. Most enter this stage fully dependent on the individuals and systems around them for food, shelter, guidance, and emotional support. Most exit with the expectation that they are economically self-sufficient. It is a transition of sense of self—a time when young adults ask questions about who they are and test their relationship with family, community, and society. This period is also a transition between systems: from K through 12 education to postsecondary, or fulltime employment.

While this stage can be full of hope and opportunity, for some it is fraught with anxiety about disappearing support systems. For example, for youth in foster care, an 18th birthday can mean an abrupt end to a home. For a young person who doesn’t have the option to stay on a guardian’s insurance, a 19th birthday means an end to health insurance. For young adults involved in the courts, it is a transition to a harsher, more punitive justice system. And for many under-skilled young adults, finding a job that pays a living wage can feel out of reach.

Of the nearly 40 million Americans between the ages of 16 to 24 in the U.S., approximately five million are neither employed nor in school. That translates to 1 in 8, more than double the rate of some Western European countries. In rural areas of the U.S., the number grows to 1 in 5. Often called “disconnected youth” or “opportunity youth,” many of these folks have experienced homelessness, substance abuse, and teen pregnancy. Still others have dropped out of the mainstream school system or been tangled up in the courts or foster systems—all of which contribute to work-limiting mental and physical disabilities and unemployment. This disconnection is not only difficult for the youth themselves, it is also costly to society in the long run: Young people who do not connect to the workforce early on tend to remain more vulnerable and reliant on government programs on an ongoing basis.

But donors have a tremendous opportunity here to intervene. The odds may be stacked against them, but when given the opportunity and support, many of these disconnected young adults find their way forward. This period of young adulthood is a time when trajectories are much more susceptible to change. New research indicates that our brains are not fully formed until we reach our early 20s. This helps explain some dubious decision-making among teens and young adults, but also reveals their potential: a remarkable ability to rapidly learn and adopt positive behaviors, skills, and habits—literally rewiring their brains. Furthermore, if young adults are more stable, personally and economically, not only do they benefit, but so do their children, who have a better shot at growing up in a supportive environment.

THE AMERICAN GAP

The U.S. rate of “disconnected youth”—defined as those between the ages of 16 to 24 who are neither employed nor in school—is twice that of some Western countries.

Rates of youth disconnection: U.S. and selected western European countries

Source: Eurostat, European Commission, http://cc.europa.eu/eurostat

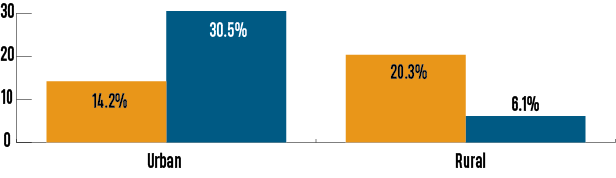

THE URBAN-RURAL DIVIDE

Although the number of “disconnected youth” is higher in urban areas, the rate of disconnection is greater in rural areas.

- Percent disconnected youth

- Percent of U.S. population

Source: Measure of America, http://www.measureofamerica.org/DY2017

“When you invest in young people—when you support, mentor, and guide them—you can change the trajectory of their life. When young people have their eyes opened to experiences and opportunities they never thought were possible, they can dream bigger and their reality can be so much more.”

-Carmen, YouthBuild Philadelphia Charter School Graduate

DISCONNECTION BY RACE/ETHNICITY

While rates of disconnection are in the double digits for all groups, they are particularly high among Native American and African American young adults.

Source: Measure of America, http://www.measureofamerica.org/DY2017

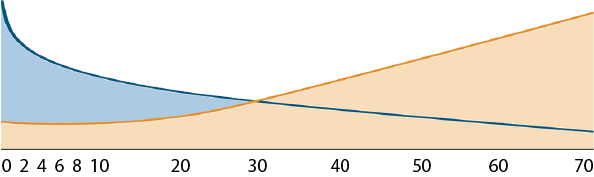

THE CHANGING BRAINS OF YOUNG ADULTS

New research indicates that our brains are not fully formed until we reach our early 20s. This fact helps explain some dubious decision-making among teens and young adults, but also reveals their potential; a remarkable ability to rapidly learn and adopt positive behaviors, skills, and habits. While the brain’s ability to change declines with age, among young adults, the potential for change is still substantial.

- The brain’s ability to change in response to experiences

- The amount of effort such change requires

Source: Levitt (2009), Harvard Center for the Developing Child

As with most antipoverty efforts, there is no silver bullet, and progress tends to be incremental. Large-scale change also requires a reexamination of systems and policies. By investing in programs that work to get disconnected youth back on track, donors help transform the futures of generations. What’s more, the savings to society are exponential: Taxpayers save an estimated $14,000 per year for each young adult that is helped out of homelessness, criminal activity, or job loss after pregnancy.

Today, thanks in part to investments by national funders and advocates, there are also clearer on-ramps and more developed programs. Therefore, now is the time for regional and local funders to help bring these approaches home, to invest in proven models, elevate best practices, and continue to support research, development, and growth of this emerging field.

In this report, we profile five organizations that have shown notable achievement in reconnecting youth: four with established track records of success for this cohort, and a newer, innovative effort that builds on the success of an established program to support poor, rural young parents. Selected for their national reach and diversity of approaches, two are focused on highly vulnerable subgroups: Youth Villages concentrates on those aging out of the foster system while the Center for Employment Opportunities services formerly incarcerated youth. The remaining three organizations are focused on connecting young adults to education and employment (Youth- Build, Year Up, and Goodwill Excel Academies).

We selected these specific organizations because of their geographic range (urban, suburban, rural) and variety of populations, including those facing additional vulnerabilities such as parenting or involvement in the courts or foster care systems. Additionally, we selected for clear philanthropic on-ramps as well as evidence of effectiveness. The organizations we highlight over the next few pages serve youth exclusively or have incorporated youth services into broader programming to show a range of approaches. While a host of other programs and approaches focus on preventing youth from disconnecting in the first place—through dropout prevention, or youth crime prevention, for example—our focus in this brief is on helping disengaged young adults reconnect.

In championing the work of these and similar organizations, donors can help young people at critical stages of their lives and assist them in reaching their untapped potential. As one such young adult described her transformation from high school dropout (because she couldn’t afford the school uniform) to exotic dancer to salutatorian of YouthBuild Philadelphia Charter School’s Class of 2014: “I really wish you could meet all the young people I know. Because, to you, my story is so amazing. But it’s a life that I’m used to. It’s all I know. If you think I’m amazing, I wish you could invest in and see the people I know, because they are phenomenal.”